Minted! Canada and Digital Cash

According to Bloomberg, Tim Lane (the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada) is "laying the groundwork to introduce a digital currency, should the need for one emerge”. What caught my eye about this story was, of course, that Canada has already had two digital currencies and abandoned both of them! The first was Mondex, the second was MintChip. Let’s have a quick chat about them.

Mondex, eh?

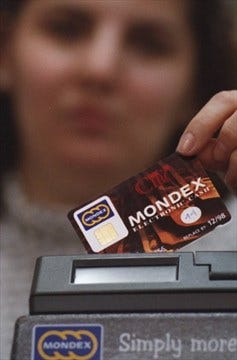

So for those of you who don’t remember what all of the fuss was about: Mondex was an electronic purse, a pre-paid payment instrument based on a tamper-resistant chip. This chip could be integrated into all sorts of things, one of them being a smart card for consumers. Somewhat ahead of its time, Mondex was a peer-to-peer proposition. The value was transferred directly from one chip to another with no intermediary and therefore no cost. In other words, people could pay each other without going through a third party and without paying a charge. It was true cash replacement.

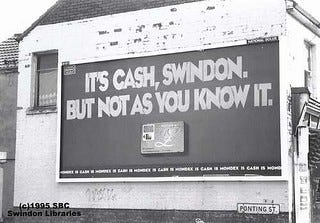

It was invented at National Westminster Bank (NatWest) in 1990 by Tim Jones and Graham Higgins. In December 1993, (NatWest) launched Mondex in a joint development pilot with Midland Bank (part of HSBC) also in the UK and British Telecom (BT) and began planning their pilot in Swindon. Swindon had been chosen as, essentially, the most average place in Britain. Since I’d grown up there, I was rather excited about this, and while my colleagues carried out important work for Mondex (e.g., risk analysis, specification for secure transfer, multi-application OS design and such like) I watched as the fever grew out in the West Country.

Unfortunately, it just never worked for consumers. It was pain to get hold of – I can remember the first time I walked into a bank to get a card. I wandered in with 50 quid and had expected to wander out with a card with 50 quid loaded onto it but it didn’t work like that. I had to set up an account and fill out some forms and then wait for the card to be posted to me. Most normal people couldn’t be bothered to do any of this so ultimately only around 14,000 cards were issued. I also pulled a few strings to get my mum and dad one of the special Mondex telephones so that they could load their card from home instead of having to go to an ATM like everyone else. British Telecom had made some special fixed line handsets with a smart card slot inside and you could ring the bank to upload or download money onto your card. I love these and thought they were the future!

(My parents loved it too, not because they could use it pay for anything but because you could put the Mondex card into the phone and press a button and hey presto your account balance would be displayed on the phone. This was amazing two decades ago.)

For the poor sods who didn’t have one of those phones (essentially, all Mondex card users) the way that you loaded your card was to go to an ATM. Now, the banks involved in the project had chosen an especially crazy way to implement the ATM interface. Remember, you have to have a bank account in order to have one of these cards and so that meant that you also had an ATM card. So if you wanted to load money onto your Mondex card, you had to go to the ATM with your ATM card and put your ATM card in and enter your pin and then select “Mondex value” or whatever the menu said and then you had to put in your Mondex card. Most people couldn’t be bothered. If you go to an ATM with your ATM card then you might as well get cash, which is what they did.

Anyway, while Swindon hogged the limelight and will forever remain a key milestone on the road to digital cash, Guelph in Canada also had a special place in the hearts of digital currency scholars because the Royal Bank of Canada and CIBC brought the Mondex technology to Canada in 1995 and then in 1997, Bank of Montreal, TD Bank, Canada Trust, Bank of Nova Scotia, National Bank of Canada, the credit unions, and Caisse Desjardins formed Mondex Canada.

It got canned at the end of 1998, having never got anywhere near critical mass.

Oh well. Remember Mintchip?

This was developed by the Royal Canadian Mint as a sort of Mondex but in mobile phones instead of smart cards. It was intended as a secure way to send and spend money online, launching the project in April 2012 and showing off its first implementation in 2014.

I was one of the judges for the MintChip Challenge competition. Vitalik Buterin, the inventor of Ethereum, rather kindly mentioned me in dispatches at the time, saying that the Mint has been watching digital currency efforts on the internet for many years now, and "on the board of the MintChip Challenge’s judges are people like David Birch, who has researched Bitcoin extensively and even spoke at the Bitcoin conference in Prague last November."

In the end, MintChip never made it to the mass market and was sold to nanopay in 2016 when the Mint decided that this central bank digital currency stuff probably wasn’t going anywhere. However, many of that team (with all of the expertise they gained in person-to-person digital cash implement in mobile phones) are still working in the Canadian payments sector today, so could hit the ground running!

So what’s my point?

Well, if the Bank of Canada really does want to lay the groundwork for digital currency, I’d be happy to point them in the direction of a fair few Canadians with some relevant expertise and experience. I might also urge them to make sure that the lessons from those early experiments with virtual Loonies aren’t lost. In particular, there are three lessons that I draw from that time when back with perfect hindsight.

The first lesson is that banks are very probably the wrong people to launch this kind of initiative. Our experiences with (for example) M-PESA, suggest that a lot of the things that I remember that I was baffled and confused by at the time come down to the fact that it was a bank making decisions about how to roll out a new product. The decision not to embrace mobile and Internet franchises, the decision about the ATM implementation, the stuff about the geographic licensing and so on. I can remember when the publicans of Exeter asked the banks to install Mondex terminals in the pubs since all of the students had cards and the bank refused on the grounds that the University’s electronic purse was only for use on campus. Normal companies don’t think like this.

(There were many people who came to the scheme with innovative ideas and new applications – retailers who wanted to issue their own Mondex cards, groups who wanted to buy pre-loaded disposable cards and so on. They were all turned away. I remember going to a couple of meetings with groups of charities who wanted to put “Swindon Money” on the card, something that I was very enthusiastic about. But the banks were not interested.)

That’s not to say that a central bank is necessarily the best home for digital currency either, but perhaps so sector-wide or cross-sector consortium might be better.

The second lesson is that the calculations about transaction costs (which is what I spent a fair bit of my time doing) actually really didn’t matter: they had no impact on the decision to deploy or not to deploy in any particular application. I remember spending ages poring over calculations to prove that the cost of paying for satellite TV subscriptions would be vastly less using a prepaid Mondex solution rather than building a subscription management and billing platform and nobody cared. I went to present the findings to a bank that was actually funding satellite TV rollout at the time, BT who were providing the backhaul and the satellite TV provider themselves. Nobody cared. The guys at the bank told me that they didn’t have the bandwidth for it (which meant, I think, that they had no interest in spending money so that another part of the bank might benefit). The banks with big acquiring operations were being asked to compete against themselves and so they didn’t care either. The transaction cost, which I thought was the most important factor, really wasn’t one of the drivers.

The third lesson is that while the solution was technically brilliant it was too isolated. The world was moving to the Internet and mobile phones and to online in general and Mondex was trying to build something that was optimised not to use of any of those. At the time of the roll-out, I had an assignment for the strategy department of the bank to provide technical input to a study on the future of retail banking that one of the big management consultancies was working on. I remember being surprised that it didn’t mention the Internet, or mobile phones or (and here’s something that I thought would be big but was also wrong about) digital TV. Most of their work as far I as could see was on redesigning the furniture in the branches.

Mondex was designed to be the lowest-cost peer-to-peer offline electronic cash system at exactly the moment that the concept of “offline” began to fade. It was not alone in failing to react to this fundamental change and it’s an interesting point to consider with hindsight: why did we make systems such as Danmont, Mondex, VisaCash and use them to compete with cash in the physical world rather than use them in the virtual world where there was no cash?

(This was clear to me very early on in the experiment and isn’t hindsight. I drew the same lesson from the Mondex pilots in Canada and the USA as well. The banks put Mondex terminals in places where they already had card terminals that worked perfectly well. You could use Mondex cards in Swindon in the places that acquired bank-issued payment cards, such as supermarkets, but not in places where digital cash had a real competitive advantage: on the Internet, in vending machines and at the corner newsagents.)

I hope I’m not breaking any confidences in saying that I can remember being in meetings discussing the concept of online franchises and franchises for mobile operators. Some of the Mondex people thought this might be a good idea, but the banks were against it. They saw payments as their business and they saw physical territories as the basis for deployment. Yet as The Economist said back in 2001, "Mondex, one of the early stored-value cards, launched by British banks in 1994, is still the best tool for creating virtual cash".

Now, at the same time that all this was going on at Mondex, there were for mobile operators who had started to look at payments as a potential business. These operators who already had a tamper-resistant smart card in the hands of millions of people and so the idea of adding an electronic purse was being investigated. Unfortunately, there was no way to start that ball rolling because you couldn’t just put Mondex purses into the SIMs, you had to get a bank to issue them. And none of them would: I expect they were waiting see whether this mobile phone thing would catch on or not.

So, for a variety of reasons, Mondex never caught on. It never got even half of the 40,000 hoped-for users in Swindon and usage remained low. And a quarter of a century on, the contactless card and the mobile phone (and in a week the combination of the two in ApplePay and GooglePay) continue to displace cash, we still don’t have a mass market cash alternative on the web (yes, I know, Bitcoin, whatever) and prepaid card propositions, while still expensive (because they use the existing debit rails), are widespread.

Canadian Digital Currency

Should the Bank of Canada simply relaunch Mondex or Mintchip then? Well, a bastard child of Mondex and Mintchip (and let’s not forget contactless pioneer Dexit launched in Toronto as well) is not such a crazy idea.

To a first approximation, everyone in Canada has a smartphone with a tamper-resistant secure chip inside it. And if Canada wants to compete with China, it has to set a high bar! Remember that Mu Changchun (deputy director of PBoC’s payments department) said back in October 2019 that the proposed Chinese digital currency can be used “without an internet connection would also allow transactions to continue in situations in which communications have broken down, such as an earthquake”. He went on to say, accurately, that "even Libra cannot do this" (because Libra, like Bitcoin needs to be online).

Now, if that doesn't sound like Mondex and Mintchip, I don't know what does.