What if S.P.E.C.T.R.E. had Spectre?

Ruh roh, as they say. Google has just published a paper outlining a serious security flaw in, to all intents and purposes, all computers. They knew about it months ago, but they’ve been waiting for Apple, Microsoft and everyone else to issue patches (which, apparently, mean an unavoidable reduction in processing speeds) before making it public. The paper sets out two “exploits” that take advantage of the flaw. These are called “Meltdown" and “Spectre”. They basically allow software to read data from other software that it’s not supposed to be able to, so that one application (let’s say, the hacker) can read data from another application (let’s say, your browser) to steal secrets.

As you can imagine, there was a great deal of media coverage about this flaw (as there should have been - it’s a huge deal). I happened to see an comment about it on Twitter, in which someone said words to the effect of “thank goodness it was found by don’t-be-evil Google and not by the bad guys”. This is a very misplaced sentiment. In the paper, the researchers clearly state that they do not know whether these exploits have been used in real attacks. Apart from anything else, Google says that the “exploitation does not leave any traces in traditional log files”.

So what if S.P.E.C.T.R.E. actually knew about Meltdown months ago and had Spectre in the Spring? How would we know? If they are really smart, then they’ll carry on stealing our secrets but cover their tracks so that we don’t know that they know. If you see what I mean.

It might be timely to remember the story of the Zimmerman telegram, a story that is mother’s milk to security experts.

You may recall that in 1917, Britain and Germany were at war. Britain wanted the U.S. to join the effort against the Axis of Edwardian Evil. The Kaiser’s ministers came up with some interesting plans: to persuade inhabitants fo the British (and French) colonies in the Middle East to launch a jihad, for example. Another scheme was to persuade Mexico to enter the war on the German side, thus dividing the potential U.S. war effort and eventually conquering it.

(At this point I thoroughly recommend historian Barbara Tuchman’s 1966 account of the affair, “The Zimmermann Telegram”.)

To execute this dastardly plot, the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. The telegram instructed the ambassador to approach the Mexican government with a proposal to form a military alliance against the United States. It promised Mexico the land acquired and paid for by the United States after the U.S.-Mexican War if they were to help Germany win the war. The German ambassador relayed the message but the Mexican president declined the offer.

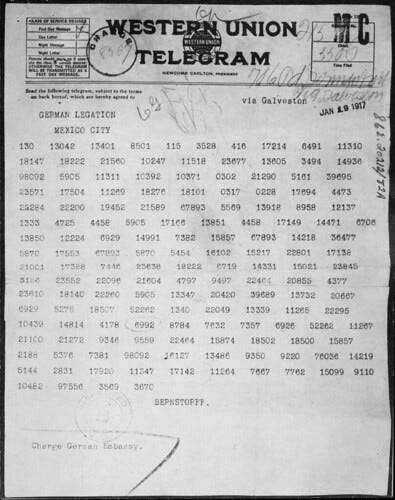

Naturally, so sensitive a topic demanded an encrypted epistle and it was duly dispatched encoded using the German top secret “0075" code. And here it is...

As it happens, “0075” was a code that the British had already cracked. Thus, the telegram was intercepted and decrypted enough to get the gist of it to the British Naval Intelligence unit, Room 40. In next to no time, the decoded dynamite was on the desk of the Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, the teutonic perfidy laid bare.

Now the British were faced with the same dilemma that faces S.P.E.C.T.R.E. with Spectre. How can you use intercepted information without revealing that there is a security flaw and that you have exploited it? Consider the options:

If the British had complained to the Germans, then the Germans would know that the British had the key to their code and they would switch to another code that the British might not be able to break for months, missing much vital military intelligence along the way. What’s more, the Americans would know that the British were tapping diplomatic traffic into the U.S.

If they did not reveal the contents, they might miss a the chance to bring the U.S. into the war.

The codebreaker's clever solution was to leak the information in such a way as to make it look as if the leak had come from the Mexican telegraph company: since the German relay from Washington to Mexico used a different code, that the Americans already knew to be broken, this was entirely plausible.

If you’re wondering what happened, well despite strong anti-German (and anti-Mexican) feelings in the U.S., the telegram was believed to be a British forgery designed to bring America into the war, a theory bolstered by German and Mexican diplomats as well as the Hearst press empire. However, on March 29th, Zimmermann gave a speech confirming the text of the telegram. On April 2nd, President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, and on April 6th they complied.

The point of this story is that stupid hackers would reveal their hand, but clever hackers would not. So the fact that, according to BBC Radio 4’s “Today” programme, the UK’s National Cybersecurity Centre says there is no evidence that the flaws have been exploited, that does not reassure me! These bugs are big.

"The Meltdown fix may reduce the performance of Intel chips by as little as 5 percent or as much as 30 — but there will be some hit. Whatever it is, it’s better than the alternative. Spectre, on the other hand, is not likely to be fully fixed any time soon."

Maybe the way forward is to assume that all machines are compromised and not fix them but instead move the security away from the processors - so going back to the idea of having a Trusted Processing Module (TPM) in every transaction, either built in to the processors (like the “Secure Enclave” in iPhones) or as a separate chip in a PC or as a smart card that is connected to the computer when you want to do something. In this, as in so many other things, Brittany Spears is a beacon to the nations. Eleven years ago I used my Britney Spears smart card (which I still have) to log on to her fan club web site securely. You can read about it here.