The Costs Of Fraud Should Be Shared

The UK should take a look at Singapore’s Shared Responsibility Framework for APP fraud.

Dateline: Woking, 7th March 2024.

I went to the Singapore Fintech Festival last year to see what was going on in the dynamic Asian market and I was not disappointed. There were plenty of interesting fintechs showing off new products and services, but to be honest what interested me most at the event was the nation’s new initiative on fraud. In a couple of weeks’ time, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) are going to implement the new Shared Responsibility Framework (SRF) for dealing with the victims of phishing scams.

Under the SRF, MAS and IMDA have established specific duties for FIs, PSPs and telcos, designed to directly combat phishing scams. This interests me because it is what banks are calling for in other jurisdictions (including the UK) where the banks quite rightly object to being forced to compensate customers who have fallen prey to scammers when other market participants, particularly social media platforms, do nothing to prevent these activities (in fact, it can be argued that they facilitate them).

In the UK consumers lost nearly half a billion pounds to authorised push payment (APP) fraud last year, according to the trade body UK Finance, more than two-thirds of which involved goods that were ordered online by consumers but did not arrive. Most purchase fraud comes from false adverts on social media platforms including Facebook Marketplace, according to Lloyds Banking Group and TSB. Some four-fifths of all TSB fraud cases involving some kind of manipulation or coercion (they refer to it as “social engineering”) came from Meta, either through Instagram, Facebook or WhatsApp.

(Interestingly, the latest figures from the UK show losses due to authorised push payment fraud, characteristic of these scams, were down some 11% while unauthorised card payment fraud went up 5% in the same period.)

The UK Way

While in the UK, four in 10 victims of fraud are already compensated by their bank (compared with 32 per cent in the US, 15 per cent in Japan and 14 per cent in Germany,), the UK’s Payment Services Regulator (PSR) extended what is known as the “contingent reimbursement model” (CRM) that was revised earlier this year to require sending PSPs to reimburse all customers who fall victim to APP fraud in most cases, splitting the cost of the reimbursement between the sending and receiving PSPs. It also requires PSPs to provide additional protection for vulnerable customers (which some people, including me, think will lead to de-banking of vulnerable customers because of the expenses involved).

with kind permission of Helen Holmes (CC-BY-ND 4.0)

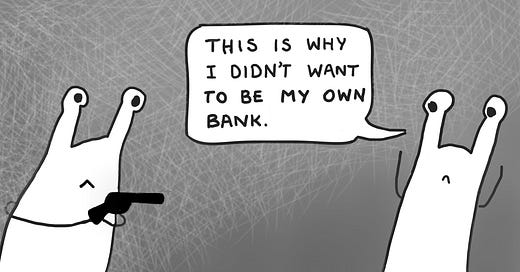

Given that that data shows that almost all APP fraud starts online or over the phone, through social media, fake messages and calls, there was considerable unhappiness in the banking sector that the technology and telecommunications providers would not be required to share the costs for reimbursing victims. In the end the regulator stood firm and the costs fall wholly on the banks.

(There was some softening in the rules though. The PSR originally proposed a maximum reimbursement level of £415,000 while PSPs were lobbying for something more like the £30,000 average loss to the frauds. The level was eventually set at £85,000 for no logical reason other than that it is the same as the deposit protection limit for consumer bank accounts.)

In response to all of this, the UK payments regulator has already said that social media groups must do more in the “war of attrition” against financial fraud on their sites and further said that the government should consider making platforms liable for compensation to victims. In fact David Geale, the interim managing director of the PSR said that introducing a levy on tech groups, forcing them to pay for the impact of scams or to fund law enforcement efforts, would be “very complicated” but was “one of the options that should be considered” by the government.

(Rather than implement a levy, I would prefer to see the government mandate KYC for advertisers and sellers on social media.)

As of now, however, it is the payments industry that pays for the scams that originate elsewhere. This is why banks and others are looking at other jurisdictions, such as Australia and Singapore, to explore different (and what lawyer Jenny Stainsby rightly called “more balanced”) models for compensation. Things are happening. Last year, for example, a number of technology and social media firms signed up to a UK Online Fraud Charter to try to do something about scams. This is a good first step, as the ecosystem needs co-ordinated action but as David Callington (HSBC UK's head of fraud) says, Big Tech needs financial incentives to make real change.

The Singaporean Way

This is why the Singaporean approach is so interesting to observers in many other countries who are studying the new framework. The essence of the new approach is that financial institutions and other ecosystem participants may have to share in reimbursing victims depending on whether the participants fail to perform their duties. Overall, banks have to fulfil five key duties, and telcos three key ones, under the SRF. If these organisations do what is necessary under the framework, consumers will bear the full losses. A few key points of this framework are:

A 12-hour cooling-off period after new device logins to e-wallets, reducing the risk of unauthorised access.

Real-time alerts for new device logins, contact detail changes, transaction limit increases, the addition of new payees and such like, allowing consumers to respond swiftly to suspicious activity.

A 24/7 self-service “kill switch,” accessible by phone or app, enabling consumers to immediately block account access if unauthorised activity is suspected.

These all seem like sensible policies given the current state of things. Fintechs should not be able to evade their responsibilities for protecting consumers (caveat emptor makes no sense in the social media era) but neither should one set of marketplace participants be made to bear full responsibility for frauds that are not their fault. And if the regulators do want to take action that will have real impact on the scale and scope of fraud they should start by bringing digital identity to the mass market so that not only does the bank know that it is really dealing with you, but you know that you are really dealing with the bank.

Are you looking for:

A speaker/moderator for your online or in person event?

Written content or contribution for your publication?

A trusted advisor for your company’s board?

Some comment on the latest digital financial services news/media?