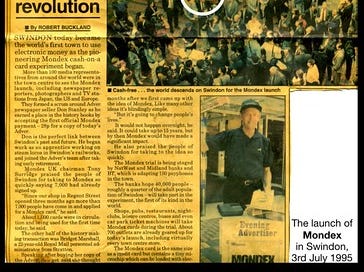

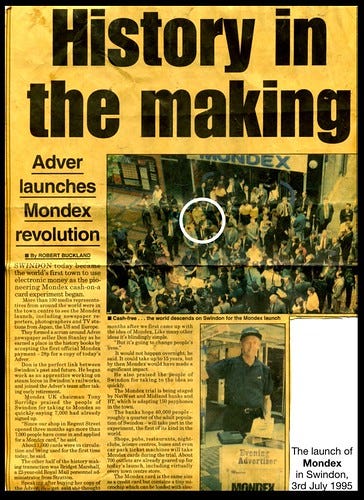

July 4th! Such an important anniversary! I look forward to it every year, and every year I spend the 4th reflecting on revolution and the course of history. I’m sure you know why, but if you don’t, well, here is a hint. It’s the front page of the Swindon Evening Advertiser from July 4th 1995, the day I finally made the front page of my home town newspaper.

(Got to see my picture on the cover, got to buy five copies for my mother…)

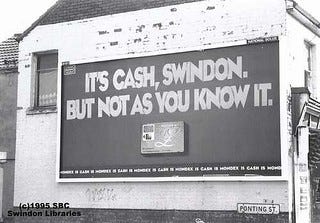

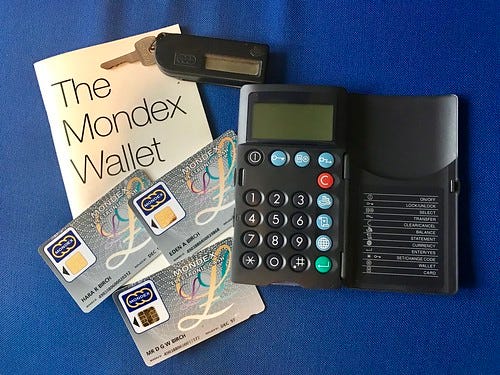

Yes, I was there on 3rd July 1995 in Swindon town centre when the Swindon Evening Advertiser vendor Mr. Don Stanley (then 72) made the first ever live Mondex electronic cash sale. It was a very exciting day because by the time this launch came, my colleagues at Consult Hyperion had been working on the project for several years! For those of you who don’t remember what all of the fuss was about: Mondex was an electronic purse, a pre-paid payment instrument based on a tamper-resistant chip. This chip could be integrated into all sorts of things, one of them being a smart card for consumers.

Somewhat ahead of its time, Mondex was a peer-to-peer proposition, which we’ll come back to later on. This meant that the value was transferred directly from one chip to another with no intermediary and therefore no cost. In other words, people could pay each other without going through a third party and without paying a charge.

It was true cash replacement, invented at National Westminster Bank (NatWest) in 1990 by Tim Jones and Graham Higgins. Swindon had been chosen for the launch because, essentially, it was the most average place in Britain. Since I’d grown up there, I was rather excited about this, and while my colleagues carried out important work for Mondex (e.g., risk analysis, specification for secure transfer, multi-application OS design and such like) I watched as the fever grew out in the West Country.

Many of the retailers were quite enthusiastic because there was no transaction charge and for some of them the costs of cash handling and management were high. I can remember talking to a hairdresser who was keen to go cashless because it was dirty and she had to keep washing her hands, a baker who was worried about staff “shrinkage” and so on. The retailers were OK about it. For example here’s a quote from news-stand manager Richard Jackson: “From a retailer’s point of view it’s very good but less than one per cent of my actual customers use it. Lots of people get confused about what it actually is, they think it’s a Switch card or a credit card”. That’s if they thought about it all.

It just never worked for consumers. It was a pain to get hold of, for one thing. I can remember the first time I walked into a bank to get a Mondex card. I wandered in with 50 quid and had expected to wander out with a card with 50 quid loaded onto it but it didn’t work like that. I had to set up an account and fill out some forms and then wait for the card to be posted to me. Most normal people couldn’t be bothered to do any of this so ultimately only around 14,000 cards were issued.

I pulled a few strings to get my mum and dad one of the special Mondex telephones so that they could load their card from home instead of having to go to an ATM like everyone else. British Telecom had made some special fixed line handsets with a smart card slot inside and you could ring the bank to upload or download money onto your card. I love these and thought they were the future! My parents loved it, but that was nothing to do with Mondex: it was because, in those pre-smartphone days, it was a way of seeing your bank account balance without having to go to the bank or an ATM or phone the branch. You could put the Mondex into the phone and press a button and hey presto your account balance would be displayed on the phone. This was amazing a quarter of a century ago.

For the poor sods who didn’t have one of those phones (everyone, essentially) the way that you loaded your card was to go to an ATM. Now, the banks involved in the project had chosen an especially crazy way to implement the ATM interface. Remember, you had to have a bank account in order to have one of these cards and so that meant that you also had an ATM card. So if you wanted to load money onto your Mondex card, you had to go to the ATM with your ATM card and put your ATM card in and enter your pin and then select “Mondex value” or whatever the menu said and then you had to put in your Mondex card. But if you go to an ATM with your ATM card then you might as well get cash, which is what they did.

It is possible that I’m not remembering this absolutely accurately, but I do remember these were two places where the hassle of getting the electronic value outweighed the hassle of fiddling about with coins: the bus and the car park. My dad really liked using the card in the town centre car park instead of having to fiddle about looking for change but it often didn’t work and he would call me to complain (and then I would call Tim Jones to complain!). I remember talking to Tim about this some years later and he made a very good point which was that in retrospect it would have been better to go for what he called “branded ubiquity” rather than go for geographic coverage. In other words it would have been better to have made sure that all of the car parks took Mondex or make sure that all of the buses took it or whatever.

So why I am wallowing in this nostalgia again? Why should more people be celebrating the Mondex Silver Jubilee? Well, look East, where the first reports have appeared concerning the Digital Currency/Electronic Payment (DC/EP) system being tested in four cities: Shenzen, Chengdu, Suzhou and Xiong’an. DC/EP is the Chinese Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

with the kind permission of Matthew Graham @mattysino

The implementation follows the trajectory that I talk about in my book The Currency Cold War, with the digital currency being delivered to customers via commercial banks. The Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China, Fan Yifei, recently gave an interview to Central Banking magazine in which he expanded on the “two tier” approach to central bank digital currency (CBDC). His main points were that this approach, in which the central bank controls the digital currency but it is the commercial banks that distribute it, is that is allow "more effective exploitation of existing business resources, human resources and technologies” and that "a two-tier model could also boost the public’s acceptance of a CBDC”.

He went on to say that the circulation of the digital Yuan should be "based on ‘loosely coupled account links’ so that transactional reliance on accounts could be significantly reduced". What he means by this is that the currency can be transferred wallet-to-wallet without going through bank accounts. Why? Well, so that the electronic cash "could attain a similar function of currency to cash… The public could use it directly for various purchases, and it would prove conducive to the yuan’s circulation”.

How could that work? Well, you could have the central bank provide commercial banks with some sort of cryptographic doodah that would allow them swap electronic money for digital currency under the control of the central bank. Wait a moment, that reminds me of something because… yep, that’s how Mondex worked. There was one big difference between Mondex and other electronic money schemes of the time, which was that Mondex used offline transfers, chip to chip, without bank (or central bank) intermediation.

Offline person-to-person transfers. That’s huge. Libra can’t do it, and never will be able to. To understand why, note that there are basically two ways to transfer value between devices and keep the system secure against double-spending. You can do it in hardware (ie, Mondex or the Bank of Canada's Mintchip) or you can do it in software. If you do it in software you either need a central databse (eg DigiCash) or a decentralised alternative (eg, blockchain). But if you use either of these, you need to be online. But with hardware security, you can go offline.

Lessons From (A) History

After all these years, the People’s Bank of China have decided to go down the Mondex route, so now seems a good time go to think back to those long ago days and see what lessons might be passed on to a new generation of electronic cash entrepreneurs. I’ll focus on three here.

The first lesson is that banks aren’t very good at launching products that compete with their existing core businesses. Consult Hyperion’s later experiences with (for example) M-PESA, suggest that a lot of the things that I remember that I was baffled and confused by at the time come down to the fact that it was banks making decisions about how to roll out a new product. The decision not to embrace mobile and Internet franchises, the decision about the ATM implementation, the stuff about the geographic licensing and so on. There were many people who came to the scheme with innovative ideas and new applications – retailers who wanted to issue their own Mondex cards, groups who wanted to buy pre-loaded disposable cards and so on. They were all turned away. I remember going to a couple of meetings with groups of charities who wanted to put “Swindon Money” on the card, something that I was very enthusiastic about. But the banks were not interested in anything other than retail payments in shops (shops who already had card terminals that didn’t take Mondex, basically).

The second lesson is that the calculations about transaction costs (which is what I spent a fair bit of my time doing) actually really didn’t matter: they had no impact on the decision to deploy or not to deploy in any particular application. I remember spending ages poring over calculations to work out that the cost of paying for satellite TV subscriptions would be vastly less using a prepaid Mondex solution rather than building a subscription management and billing platform: Nobody cared, because reducing costs for merchants was no-one in the banks’ goal.

The third lesson is that while the solution was technically brilliant it was too isolated. The world was moving to the Internet and mobile phones and to online in general and Mondex was trying to build something that was optimised not to use of any of those. Thinking about it now, it seems odd that we made cash replacement systems such as Danmont, Mondex, VisaCash and used them to compete with cards in the physical world rather than target them where cash was a pain, such as vending machines and web sites. I hope I’m not breaking any confidences in saying that I can remember being in meetings discussing the concept of online franchises and franchises for mobile operators. Some of the Mondex people thought this might be a good idea, but the banks were against it. They saw payments as their business and they saw physical territories as the basis for deployment.

(Yet as The Economist said back in 2001, "Mondex, one of the early stored-value cards, launched by British banks in 1994, is still the best tool for creating virtual cash".)

Now, at the same time that all this was going on at Mondex, we were working for mobile operators who had started to look at payments as a potential business. These were mobile operators who already had a tamper-resistant smart card in the hands of millions of people and so the idea of adding an electronic purse was being investigated. Unfortunately, there was no way to start that ball rolling because you couldn’t just put Mondex purses into the SIMs, you had to get a bank to issue them. And none of them would: I expect they were waiting see whether this mobile phone thing would catch on or not.

Well, here we are. Mobile phones have caught on, and the People’s Bank of China are using them to deliver two-tier central bank digital currency into the mass market. I am pretty sure that they will have learned from the Mondex experiments in Manhattan and Guelph, in Hong Kong and in Sydney. The Mondex Silver Jubilee will be celebrated in a way that could never have been imagined on 4th July 1995: with central bank digital currency spreading across Shenzen rather than Swindon.