The great Chinese money experiment is over

The Chinese were first with the great transition from commodity money to paper money. They had the necessary technologies (you can’t have paper money without paper and you can’t do it at scale without printing) and, more importantly, they had the bureaucracy. In 1260, the new Emporer Kublai Khan determined that it was a burden on commerce and drag on taxation to have all sorts of currencies in use, ranging from copper coins to iron bars, to pearls to salt to gold and silver, so he decided to implement a new currency. The Khan decided to replace metal, commodities, precious jewels and specie with a paper currency. A paper currency! Imagine how crazy that must have sounded!

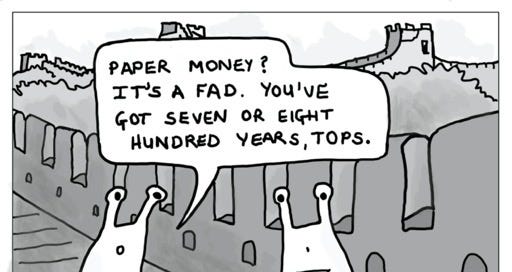

with kind permission of TheOfficeMuse (CC-BY-ND 4.0)

Just as Marco Polo and other medieval travellers returned along the Silk Road breathless with astonishing tales of paper money, so modern commentators (e.g., me) came tumbling off of flights from Shanghai with equally astonishing tales of a land of mobile payments, where paper money is vanishing and consumers pay for everything with smartphones.

[bctt tweet="China was first in to paper money and eight hundred years later looks like being first out of it." username="@dgwbirch"]

This thinking has been evolving for some time. Back in 2016, the Governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), Zhou Xiaochuan, set out the Bank's thinking about digital currency, saying that it is an irresistible trend that paper money will be replaced by new products and new technologies. He went on to say that as a legal tender, digital currency should be controlled by the central bank and after noting that he thought it would take a decade or so for digital currency to completely replace cash in China, he went to state clearly that the bank was working out “how to gradually phase out paper money”. Rather than simply let the cashless society happen, which may not led to the optimum implementation for society, they were developing a plan for a cashless society.

As I have written before, I don’t think a “cashless society” means a society in which notes and coins are outlawed, but a society in which they are irrelevant. Under this definition the PBOC could easily achieve this goal for China. But how will they do it? I got a window into the tactics when I listened to Kevin C. Desouza (Professor of Business, Technology and Strategy in the School of Management at the QUT Business School, a Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Governance Studies Program at the Brookings Institution and a Distinguished Research Fellow at the China Institute for Urban Governance at Shanghai Jiao Tong University), someone who has pretty informed perspectives. I heard him in conversation with Bonnie S. Glaser (senior adviser for Asia and the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS) on the ChinaPower PODCAST. Kevin and Bonnie were discussing China's plan to develop a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). I have looked at China’s CBDC system (the Digital Currency/Electronic Payment, DC/EP) in some detail and have speculated on its impact myself, so naturally I wanted to double-check my views (coming from a more technological background) against Kevin and Bonnie's informed strategic, foreign policy perspective.

One particular part of their discussion concerned China’s ability to advance in digital currency deployment and use because of the co-ordinated plans of the technology providers, the institutions and the state. The technological possibilities are a spectrum, there are a wide variety of business models and there are many institutional arrangements to investigate, balance and optimise. Take, for example, the specific issue of the relationship between central bank money and commercial bank money. Yao Qian, from the PBOC technology department wrote on the subject in 2017, saying that to “offset the shock” to commercial banks that would come from introducing an independent digital currency system (and to protect the investment made by commercial banks on infrastructure), it would be possible to “incorporate digital currency wallet attributes into the existing commercial bank account system" so that electronic currency and digital currency are managed under the same account.

This rationale is clear and, well, rational. The Chinese central bank wants the efficiencies that come from having a digital currency but also understands the implications of removing the privilege of money creation from the commercial banks. Thus you can see the potential problem with digital currency created by the central bank, even if it is now technologically feasible for them to do so. If commercial banks lose both deposits and the privilege of creating money, then their functionality and role in the economy is much reduced. Whether you think that is a good idea or not, you can see that it’s a big step to take. Hence the PBOC position, reinforced by Fan Yifei, Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China writing that the PBOC digital currency should adopt a “double-tier delivery system” which allows commercial banks to distribute digital currency under central bank control. I don’t doubt that this will be the approach adopted by the Federal Reserve when the US eventually decides to issue a digital dollar, which is why we in the West should be studying it and learning from it.

I’m fascinated by China’s long experiment with paper money and its imminent demise. This will come about not because of Bitcoin or Libra but because the PBOC has been strategic in its thinking and tactical in its governance, co-ordinating practical solutions the will make digital currency work to the benefit of the nation. Their comments on the topic from 2016 to now have been consistent. Digital currency is coming and China will take the lead in digital currency just as it did in digital paper currency.

[This is an edited version of an article that first appeared on Forbes, 9th August 2020.]