Duty of Care

The U.K.’s new approach to financial services regulation cannot deliver without AI.

Dateline: Melbourne, 11th August 2023.

At the end of last month, the UK’s new regulations around consumer outcomes came into effect. These regulations, known as the "Consumer Duty” regulations, require financial services organisations to act in good faith, avoid foreseeable harm and help customers to achieve their financial objectives. They also require organisations to provide customer support that is “responsive and helpful". Now, I am not a lawyer, so I don’t know what “good faith”, “foreseeable” or “helpful” mean, but even so I cannot see how organisations will be able to deliver any of these outcomes cost-effectively without using AI. But given that the customers will be bots anyway, that’s probably a good idea.

Chats With Bots

One of the reasons why I think AI-to-AI connections are the only way to make this new duty work is that the outcomes depend to a large extent on customer understanding and providing customers with the information that they need to make decisions. ChatGPT and its brethren can speed through emails and instant messages, web chats and social media posts to review the language, wording and structure used to detect compliance issues. For example, the bots may detect vague or potentially misleading language which fails to properly inform consumers.

I have to say that it is not clear to me that informing consumers will actually help with outcomes because some years ago I was involved in a research project looking at obtaining informed consent from British consumers. The conclusion, as I recall, was that while obtaining consent was straightforward, obtaining informed consent was an almost insurmountable barrier to business. Remember, the general public have little grounding in mathematics, statistics, portfolio management and the history of investments. Hence it seems to me that the money spent on trying to inform the public about the difference between the arithmetic mean and the mode might be better spent on commissioning and certifying bots capable of making informed decisions on the customers' behalf.

(And when it comes to the provisions about value – that products and services should be sold at a price that reflects their value and that there should be no excessively high fees — I have literally no idea how to judge whether a price is appropriate but presumably lawyers do, so that’s OK.)

What will this duty of care mean in practice for an average consumer such as myself? Well, one immediate impact will be on our savings. A common complaint of customers is that banks do not offer the best savings rates to existing customers and that they tempt people in by offering high rates for an initial period only. A combination of the demands of the duty of care, together with the practicalities of sweeping accounts, variable recurring payments (VRPs) in open banking and a little bit of machine learning should mean that British consumers are assured a much better value, and that the banks will have to work harder.

The Financial Conduct Authority CEO Nikhil Rathi said last year that he was keeping a “beady eye” on banks. The new Duty will heighten scrutiny on how actively banks shepherd customers into products offering better rates. Consumer inertia (or lack of confidence in making financial decisions, as the banks prefer) now becomes a bank problem rather than a consumer problem.

with kind permission of Helen Holmes (CC-BY-ND 4.0)

What should the banks do in response then? There is no choice but to turn to AI. McKinsey reckon that ChatGPT and its ilk will impact all industry sectors but they single out banking as one of the sectors that could see the biggest impact. Estimating that the technology could deliver value equal to an additional $200 billion to $340 billion annually if the use cases they look at were to be fully implemented.

These figures do not seem hyperbolic to me, considering that the baby steps are yielding impressive results. At the Australian bank Westpac productivity grew by almost a half, with no reduction in code quality, when software engineers were aided by generative AI compared to a control group that performed the same tasks exclusively by hand.

(Incidentally, Emad Mostaque, the CEO of Stability AI, recently said that "There will be no programmers in five years”. This does seem somewhat hyperbolic, but probably not by much.)

One of the biggest use cases that McKinsey identified in banking was the conversion of legacy code. So, should a bank spend years using ChatGPT to rewrite thousands of lines of COBOL to try to optimise the product selection for individual consumers? Surely it will undoubtedly be more cost effective to allow AI to review the customers circumstances, the changing environment and the available products to not only advise customers on what the best products might be but to automatically move customers’ funds around.

This is where the new breed of ChatGPT-like Large language models (LLMs) can make a difference. As Bain Capital Ventures point out in their recent note on the topic, traditional AI is leveraged heavily to take care of the 80% of requests that are straightforward (eg, “When is my bill due?”) but not the 20% of requests that are bespoke and actually represent 80% of the cost (eg, “Should I refinance my mortgage now or wait until next year?”). The latter requires customer service representatives, but they are slow, expensive and don’t always have the right information readily accessible to address the customer inquiry.

Explaining AI

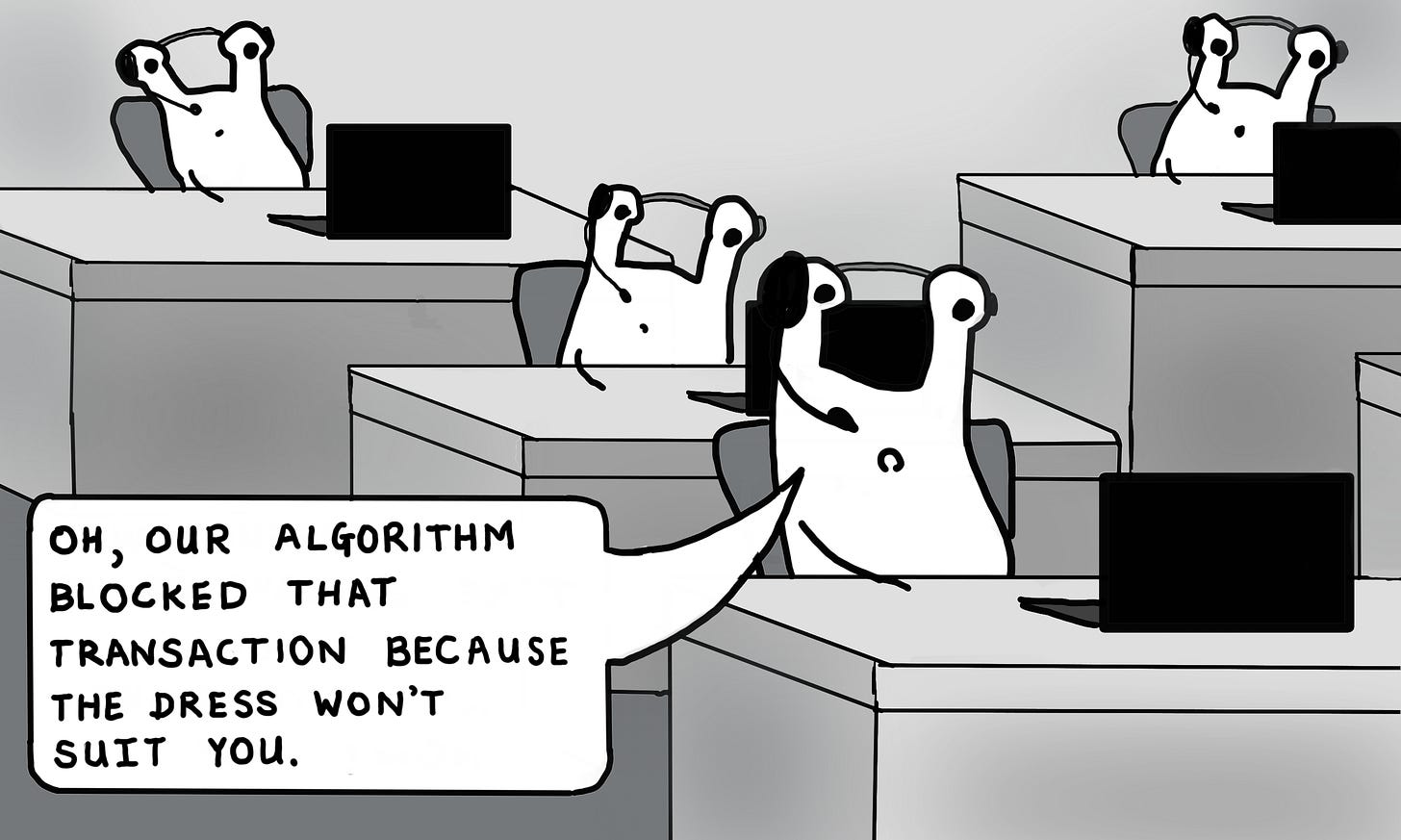

Banks must, however, be careful about just how the Duty of Care is implemented using AI. Last year’s Bank of England discussion paper on AI pointed out that while the Consumer Duty does not prevent firms from adopting business models with different pricing by groups (such as risk-based pricing), certain AI-derived price-discrimination strategies could breach the requirements if they result in poor outcomes for groups of retail customers. As such, firms should be able to monitor, explain, and justify if their AI models result in differences in price and value for different cohorts of customers.

There are legal requirements in GDPR, which states that when individuals are impacted by decisions made through “automated processing,” they are entitled to “meaningful information about the logic involved” and similarly in CCPA (the California Consumer Privacy Act) which says that users have a right to know what inferences were made about them by AIs.

What all of this means is that the real need is for “explainable AI” (or “XAI”) in financial services. As IBM explain it, XAI is one of the key requirements for implementing responsible AI, a methodology for the large-scale implementation of AI methods in real organizations with fairness, model explainability and accountability. They go on to say that in order to adopt AI responsibly, organizations need to embed ethical principles into AI applications and processes by building AI systems based on trust and transparency.

(This is definitely outside my envelope, but as an informed observer it seems to me that there is a lot of work to be done here.)

Do Your Duty

The new U.K. Consumer Duty is a huge regtech/fintech opportunity. Take a look at the report on "FCA Consumer Duty: Business Burden or Golden Opportunity" prepared by U.K. fintech Moneyhub. They do a great job of exploring the value-creating uses cases around compliance with each of the requirements. This makes a lot of sense to me: If you are building a machine-learning model to use data from multiple sources to assess whether a consumer is vulnerable to frauds, for example, you can use that same model to help the customer build resilience against other external changes (eg, changes in employment status).

This approach helps with the Duty to show that the organisation’s products and services should be fit for purpose and help the organisation to work with others toward the desirable goal of delivering financial health rather than a collection of loosely-related financial services.

Are you looking for:

A speaker/moderator for your online or in person event?

Written content or contribution for your publication?

A trusted advisor for your company’s board?

Some comment on the latest digital financial services news/media?

As usual, I fully agree with everything you say. As the European Commission seems to be saying on how to deal with APP fraud in the context of PSD2 revision: so much more is possible for banks, using machine learning/AI. A little incentive to do a better job here in the shape of a bit more liability seems to be appropriate. See their recent PSD3/PSR proposals. Of course all this is easier said than done, and time is working against the banks I believe. GenAI developments are taking place at an incredible pace, and fraudsters will rather sooner than later be successful in deep faking biometrics and thus bypassing security (in fact, they already are to a certain extent). "Yes, but is stil early days, you can demonstrate it in a controlled lab environment, and it will take time for criminals to produce at industry scale." Reminds me of the research by Ross Anderson in the first decade of this century and the bank's reflexes, see e.g. https://krebsonsecurity.com/2012/09/researchers-chip-and-pin-enables-chip-and-skim/. I'm scared s***tless if I try to image what AI in the wrong hands can do. Not only in payments, by the way. And yes, I know, it will help finding cures for cancer too. That is the terrible dilemma here: is there still time to balance the tech optimist creativity push (sort of) renegade train to the AI goldrush (what a great stunt scene in "Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning"!!) and some thinking about how to mitigate the inevitable negative consequences? Rhetorical question I guess; hope to see the happy end in 2024 in Part II when Ethan brings The Entity under control .....