Davo Polo

I set off for Hangzhou and Money2020 China as a modern-day Marco Polo, intent on coming back home to regale the subjects of Her Majesty with fanciful tales of a far-away place where people use their mobile phones to pay for things and nobody uses paper money any more, much as Marco Polo himself would have regaled the inhabitants of Venice with his tales of (as it happens, the same) far-away place where people used paper money to pay for things and nobody used copper bars, cowrie shells or coins any more.

Hanging with Tracey Davies, the President of Money2020.

My travels were a lot easier than Marco's because for one thing I was able to fly directly to Shanghai whereas it took him years to get there and for another thing because everyone (and I mean everyone) has a smartphone, and their smartphones all have translation applications that convert spoken English to written Chinese and spoken Chinese to written English. My first experience of this was at Shanghai airport when the driver meeting me spoke into his phone and then presented me with a screen saying “do you know this person?” and holding up a sign with “Chris Skinner” on it. Naturally, I took the phone and said into the microphone “no, I’ve never heard of him and I’ve never read any of his books either” but it was too late as the driver had just seen him in arrivals.

Flying the flag for Brexit Britain

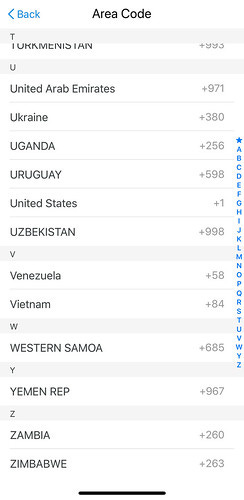

My first step on the road to amazing my peers back home was to get a working AliPay or WeChat account. I’d forgotten my AliPay password so I decided to sign up for a new account. Unfortunately you can’t get an AliPay account with a UK phone number. An American phone number, yes. An Australian phone number, no problem. A Burkina Faso phone number, Bob’s your uncle.

Alipay options

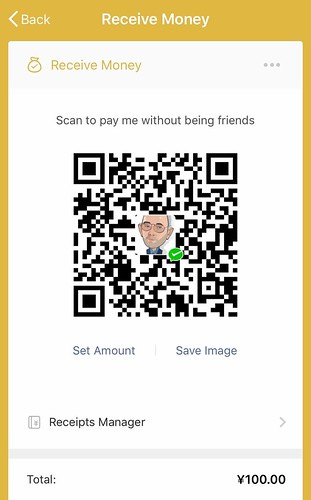

As it seemed like a UK phone number was beyond the pale, I decided to get WeChat instead. I activated my WeChat money function by linking my account to a couple of my credit cards.

Activiating WeChat Money

None of my cards worked in this context, but it didn’t matter because once the money function is activated you can just give people cash and ask them to send the same amount via WeChat, thus topping up via a system of human Qiwi terminals. One of the women that kindly agreed to do this for me, on being handed a couple of RMB 100 notes, told me that it was the first time she’d touched paper money for at least a year.

Woot! You can pay me using WeChat right now if you want to.

(China was the first in to printed means of exchange and they are close to being first out, close to being the first nation-state where notes and coins are economically irrelevant and post-functional cash will be the only kind most people ever possess. It looks as if China’s 800 year experiment with paper money will soon be over.)

Actually, it turns out that my stories of mobile phone payments are almost completely uninteresting - I wish you’d told me before, frankly - because everyone has now heard about WeChat and AliPay, everyone understands the transformational nature of their payments platforms and everyone has seen the ubiquity of QR codes. The one time we tried to use NFC, ApplePay and that totem of Western Civilisation, the iPhone (which is, of course, made in China) to pay for something, it didn’t work. App and pay, frankly, is beating tap and pay.

A payment expert witnesses the failure of tap-and-pay

(China was early into NFC, with China Mobile doing plenty of experiments in the field. Further back, Hong Kong was the birthplace of the contactless mass transit card, the Octopus scheme. I note that the Hong Kong MTA has just awarded a contract for QR code ticketing. It looks as if China’s 25 year experiment with contactless will soon be over.)

Ron Kalifa talking about value-added merchant services

As for the conference itself, I particularly enjoyed Worldpay vice-chairman Ron Kalifa’s fireside chat. He said that in general people were underestimating the impact of open banking and I am certain that he is right. He also presented Worldpay’s annual report on payment trends worldwide, which was very interesting as you might expect.

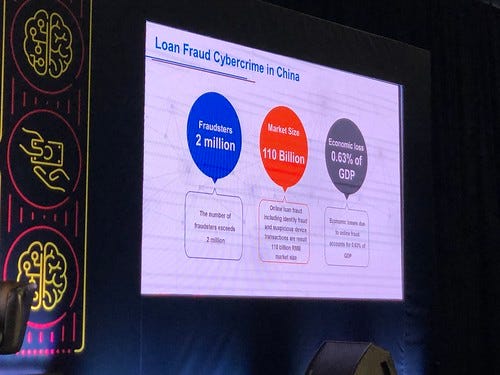

One of the factors central to the evolution of payments is security and so I always enjoy presentations around fraud. In China, these have scary large numbers attached to them, but you have to take into account the size of the Chinese economy. According to the back of my envelope, Chinese cybercrime losses are lower than in many other countries.

Real, and scary, fraud numbers

Given the widespread use of scores of one form or another to determine trustworthiness it is no coincidence that China sees a rise in frauds relating to the manipulation of these scores. Without commenting on the benefits or otherwise of such models (most Brits, myself included, can only think of Black Mirror when social scores are discussed) it is worth making the point that preventing “gaming” of these scores while preserving individual privacy means dealing with paradoxes that might well be resolved through the use of cryptographic techniques that have no conventional analogues and are therefore difficult for policymakers to bear in mind.

Reputation fraud in action

Most of what I found thought-provoking, both in the presentations and the water cooler discussions, was to do with business models rather than new technologies. The new technology that fascinated me most was the toilet in my hotel room. The lid opens automatically when you walk into the smallest room and once you have settled onto the warmed and padded seat you are faced with a control panel (shown below) that gives access to a variety of functions, all of them wonderful. Next time someone tells you that a cashless economy is as likely as a paperless bathroom, tell them that I’ve experienced both, and they are both awesome.

Toilet 2.0

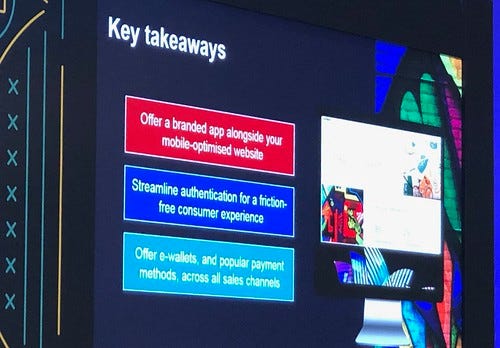

The new business models emerging in a regulated, platform-centric, dynamic market are what we should be studying. We might choose to implement some of these models in a slightly different way taking into account the varying cultural norms around security and privacy, but the idea of separating payments from banking and then turning payments into platforms, and then using these platforms to acquire customers at scale for other businesses is certainly very interesting.

This is what a smartphone-centric platform looks like

These new models, of course, centre on data and value-adding using that data. When people pay for everything with their mobile phone, they lay down a seam of data that is waiting to be mined. Despite this, the convenience of the mobile-centre platforms is so great that people are clearly willing to put privacy concerns to one side. I chaired a great session on privacy with CashShield, Symphony and eCreditPal with, I think, gave out a very comforting message: if you build services with privacy in the first place, then actually complying with GDPR and other global regulations is actually not that much of a problem.

One more thing that struck me about the context for these developments that it seems to me that China is making its e-money regulation more like the EU's. With an EU electronic money licence, the organisations holding the funds must keep them in Tier 1 capital and are not allowed to gamble the customer’s money, whereas in China there was no such restriction. Now the People’s Bank has said that from January 2019 the Chinese operators will have to hold a 100% reserve in non-interest bearing deposits at a commercial banks, a decision that will likely cost the main players (Tencent and Alipay) a billion dollars or so in revenue.

Anyway, a big thank you to the Money2020 for giving me the opportunity to take part in this event! It was lovely to meet so many new people and see so many new perspectives, even if I did have to spend some of the time in a jazz bar.

All in all, I wouldn’t change my job for all the tea in China, much of which you can see in this picture of the plantations outside Hangzhou.

Looking forward to next year already.