Dateline: Woking, 10th October 2024.

Do you think that getting rid of cash will reduce crime or increase it? We can look at Scandinavia for indicators, since there are a great many people in Scandinavia who cannot remember when they last used cash. Cash-related crimes such as bank robbery are down (twenty years ago Denmark had 200 bank robberies per annum, last year it had none) as is tax evasion. The Swedish black market appears to have contracted, just as cashless campaigner Bjorn (from ABBA) and others had hoped.

Different Kinds Of Crime

The presence of cash means the presence of criminals and many of them are violent. Not only guns, but all sorts of weapons. This guy did not smash his car through the doors of a grocery store in England to threaten staff and demand credit card receipts. He demanded cash.

(It’s not purely an English problem. There were nearly 900 robberies using a vehicle as a weapon in the US in 2022.)

In largely cashless Sweden, online crime has surged, with criminals taking more than $100m in 2023 through a variety of scams. Does this $100m make Sweden a “high crime” country as the article implies? No, it does not. I would think that Swedish citizens are more concerned about violent gang warfare and a tripling of the murder rate, but for comparison according to UK Finance the equivalent scams in the UK were well over $1 billion back in 2022.

While cash attracts crime, then, the end of cash of course does not mean the end of crime. But it does mean that we have to do proper risk analysis on its replacements, whether these are going to be:

Electronic money (e.g., instant payments in the UK, where authorised push payment fraud is out of control and is already more than card fraud);

Electronic cash, in the form of public (central bank) digital currency or private digital currency; or

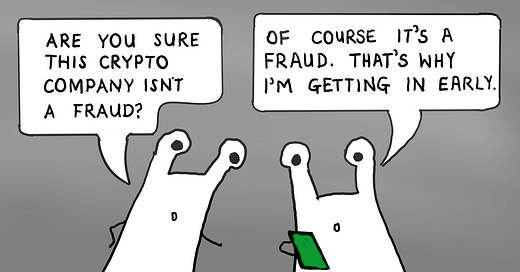

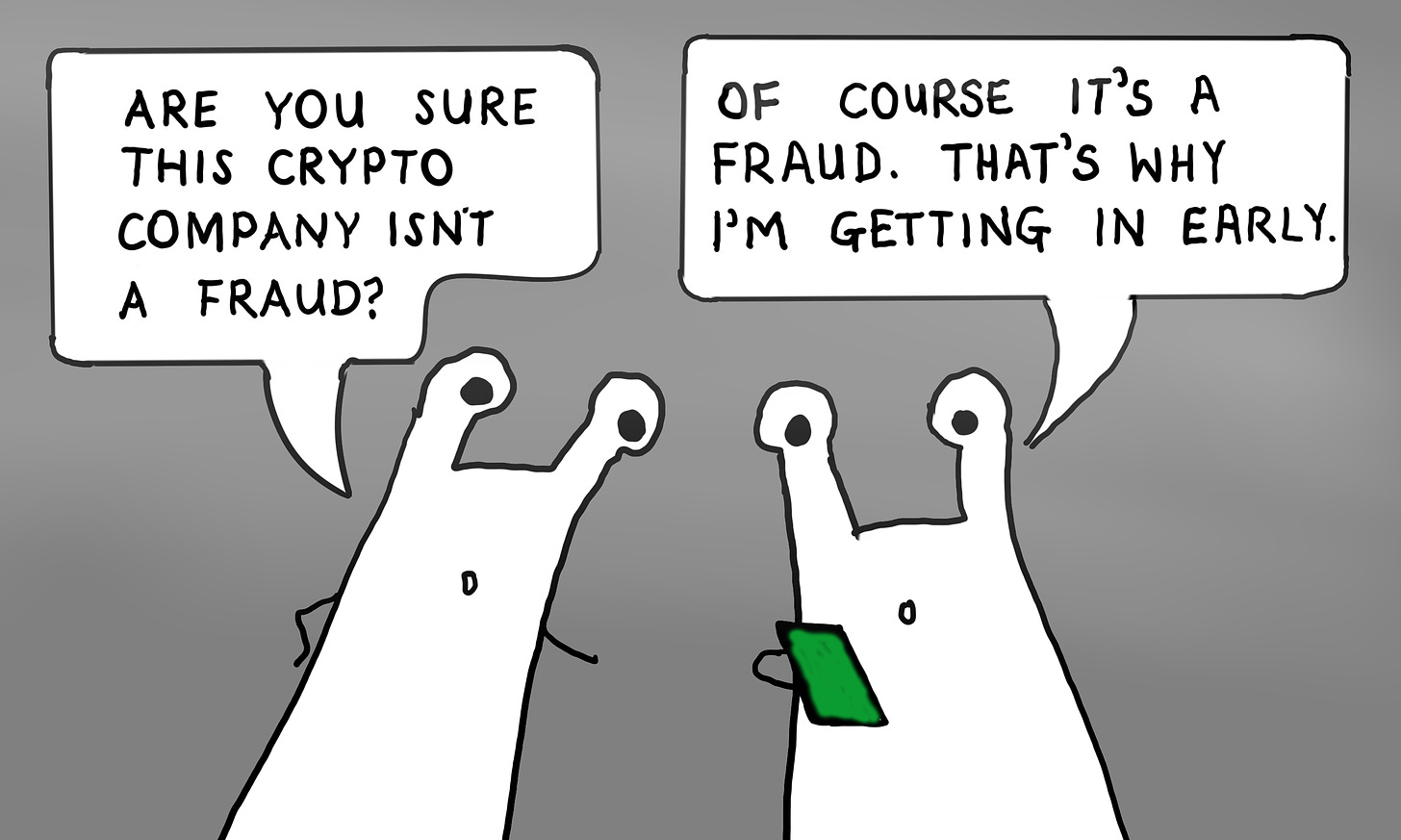

Cryptocurrency, a sector that is rife with crime.

Each of these alternatives has positives and negatives and none of them are crime-free, of course. In particular, the spectrum of crime evolving around cryptocurrency is fascinating and frightening.

with kind permission of Helen Holmes (CC-BY-ND 4.0)

Some cryptocrimes are straightforward and predictable. The frictionless nature of cryptocurrency transactions makes them an obvious accessory. For example: a chap in Scotland has just been convicted of possessing stolen goods (i.e., stolen property, not money, and important point to make although not the subject of this piece) after violently assaulting a man and forcing the victim to transfer bitcoin to him. I am sure that this sort of thing is distressingly common, even if it is not always reported, and it has been going on for a while. A typical case is that of whale Zaryn Dentzel, who was subject to a home invasion ordeal that lasted several hours during which he was beaten and forced to give up the password to his cryptostash. Talking about whales, by the way, one of them recently had a quarter of a billion dollars stolen in a scam, although the perpetrators were traced after they accidentally shared an address that has been used to purchase luxury clothing (pro tip: don’t use your stolen crypto to order stuff for delivery).

(I did note with interest a recent “combo” cash/crypo robbery in Texas, where an elderly woman who was being scammed into feeding her savings into a Bitcoim ATM was robbed by depressingly traditional muggers who grabbed her envelope full of cash and scarpered.)

The most recent FBI figures indicate the Americans lost more than $5.6 billion due to cryptocurrency scams last year, approximately half of all the losses from financial fraud last year, an increase by half over the previous year. I think we can assume that replacing cash with crypto will not enhance public safety or security.

Thinking About Welfare

The Asian Development Bank that found that more fintech reduces thefts by reducing cash holdings (and, rather interestingly, providing more job opportunities). What’s more, a survey to estimate the cost of theft for households suggested a further unexpected source of welfare gain from the development of fintech: an improvement in public security. American Banker says that violent bank crime has become increasingly less common but there were still 1,612 bank robberies in the US in 2022 whereas in Sweden there were… none.

(Not all bank robberies involve shotguns, by the way. There was a robbery in London where the robber posed as a security guard, wandered into a branch of Santander, flashed a fake ID and walked out with two boxes of cash with a total of £150,000 in them. Identity really is the new… well, you know.)

Interestingly, one of the problems in Sweden is the prevalence of BankID. Almost everyone in Sweden uses their “BankID” for everything. Over the last couple of decades it has become integral to Swedish life, used more than twice a day by every adult Swede for everything from filing tax returns to buying bus tickets. Signicat’s excellent report “The State of Digital Identity in the Nordics 2024” notes that this has led to problems with social engineering attacks that fooled consumers into accepting "rogue authentication request” in the BankID app but the recently launched "digital ID card" in the app (activated by reading a Swedish passport or national ID card within the app) should help. It works by presenting a dynamic QR code that can be scanned to digitally verify identity and create digital transaction record is designed to cope with these attacks, creating a link between the service and the app.

The conclusion I draw from all of this is, as you might expect from someone with a lifetime in consultancy, nuanced. Yes, of course the presence of cash induces crime and so the absence of cash reduces crime, or at least it reduces some kinds of crime. The reverse is also true: If there is more cash floating about then there will be more crime, particularly opportunistic crime. This is why people who are trapped in a cash economy are so vulnerable to theft, loss and shakedowns and why the idea that we need to keep cash in order to support less well-off members of society is misplaced. UK research indicates that families who trapped in the cash economy are hundreds of pounds per annum worse off than families who are not. The reasons are multiple: the cost of cash acquisition, the inability to pay utilities through direct debit, exclusion from online deals and a variety of losses.

(There’s something unfair about this. People who choose to exist in a cash economy to avoid taxes, such as drug dealers, are cross-subsidised by the rest of us whereas people who have no choice but to exist in a cash economy are not cross-subsidised at all.)

Yes And No

There is no doubt that the trajectory is towards cashlessness. In Marqeta’s 2024 State of Payments Report, nearly three-quarters of U.S. consumers said that they were not concerned about moving towards a cashless society. In fact, more than a quarter of respondents said it feels awkward to pay with cash, with nearly half of those ages 18 to 34 expressing this sentiment.

However, if we reduce cash in the absence of any kind of overall strategy towards cash and cashlessness (which would necessarily include some form of digital identity infrastructure as well as some form of digital money infrastructure) then organised crime will simply move from the physical to the virtual and begin looting bank accounts instead of cash registers. Coming from a technological direction, I am optimistic that we can reduce both cash and crime by taking a more strategic approach to the issues of identification, authorisation and authentication in an always-on, always-connected society.

Are you looking for:

A speaker/moderator for your online or in person event?

Written content or contribution for your publication?

A trusted advisor for your company’s board?

Some comment on the latest digital financial services news/media?